The thing to understand about cinema — and any art by extension — is that every story and every form is ultimately a mission, and that mission is to try to make sense of the world.

In such an interpretation of this chaotic, uncontrollable human tendency called creativity, a movie is no different from a piece of scholarly writing, and a science book is no different from a poem. We use our cognition to interpret life and give birth to colorful definitions. We then use those definitions to come up with words and names. And we then use those words and names to retell stories of humanity over and over again.

So no matter where one particular piece of art stands upon this timeless tapestry, and no matter how much you need to chip away at its deceptive tendrils to reach that core, every story is always on a mission, and that mission is to try to make sense of the world by making a point.

A great movie is one that manages to effectively get the point across. It inspires people to act and it rekindles their thoughts. It allows them to break free of the mundane and contemplate ideas and ideals beyond the frivolity and pettiness of their own inconsequential dilemmas. It gives birth to hope and paints a picture of what life has to offer beyond the horizons of human folly.

One would hope, then, that when we’re talking about a movie not only out to make that point but essentially owing its existence to that point, we would have nothing but praise to heap on its creators.

Alas, that couldn’t be further from the truth when it comes to the so-named and so-titled Intoxicated by Love. Because it matters little if the subject matter begs to find a long-overdue depiction on this tapestry. It matters little if the point of your story is far more important than the overwhelming majority of filler garbage out there; When you can’t make it work, it simply doesn’t work.

Yet that, in and of itself, shouldn’t compel us to overlook the effort entirely.

Intoxicated by Love is a mediocre movie on almost every level. The convoluted storyline hardly comes together by the end of the film. None of the characters really get their moment in the spotlight, and none of their character arcs reach a fulfilling conclusion. In fact, characterization is almost non-existent in this ambitious new flick by Hassan Fathi, a tragedy exacerbated by the fact that it’s supposed to revolve around one of the most important figures in the history of literature and poetry.

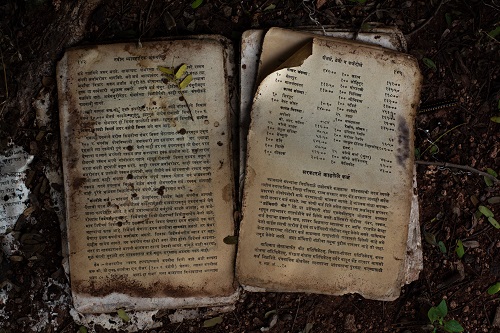

Rumi (or Mowlana as we refer to him in Persian to mean “our spiritual leader”) is a man whose reputation precedes himself, even to the uncaring post-modernist incapable of finding a minuscule part in his soul that can understand and appreciate beauty. Rumi was, is, and will be the great diviner of ages, and the only reason his words aren’t more widespread today is because the supposed guardians of his legacy — and that would be referring to me and my esteemed countrymen — have failed to give it a new coat of paint for modern audiences.

That was supposed to change with Intoxicated by Love. At least, that’s what we were hoping for when we realized the character was finally joining the long list of historical figures to make their make-believe debut on the silver screens. But the movie we got fails to depict Rumi as a figure even worthy of attention, let alone a sage whose teachings should still be relevant today.

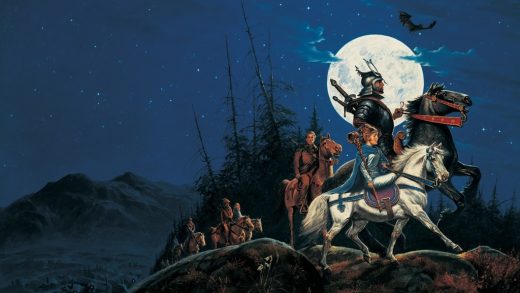

But something sets Intoxicated by Love apart from the other shallow and horrid movies we get to watch nowadays. Those films you can toss aside without a second thought and never look back, but I seem unable to do the same with this particular outing. How strange it is to realize that form loses its potency the moment substance, real substance, comes along. For it can only be a testament to Shams Tabrizi and Mowlana’s mystic magnetism that their very presence on the big screen, robed just so, compels me to dream of a day when a master craftsman picks up their tale again and this time does it justice.

Because if anything, this is a story that will be and ought to be revisited in the future. Perhaps by hands that not only adore the insanity that moved our Darvish mystics to “hold in one palm the tangled mane of the adored and in the other a grail of mead, and dance senselessly away and unto this gathering with no heed,” but also hail from the same cloth that bore them in a place long forgotten and a time long past.