It is only fair for me to note, before we even begin, that I fell in love with Alan Wake 2 long before I began to ponder all the philosophical questions, psychological implications, and mystical ties sitting at the heart of Sam Lake’s new absurdist soup. But if there’s one thing that makes a work of art more worthy of acclaim, it’s the welcome, but often surprising depth that oh-so rarely comes with retrospect.

And trust me; there’s a lot of that to be uncovered so far as Alan Wake 2 is concerned. Remedy prides itself in the ability to weave gameplay and story together in a great avant-garde tapestry and this new release is no exception, but what makes Alan Wake 2 so special is the slippery balance that often ends up being the difference between a confusing amalgam of incongruous ideas and a sure-footed tale rooted deep in profound, defensible, and universally recognized schools of thought.

That is what Remedy hopes will suddenly click together for its fanbase. That from shooting your way through monstrous apparitions of shadow in a very Jungian rendition of New York City to the Lovecraftian horror of caldera lakes and idyllic rural towns, players may very abruptly come to a halt and realize that the overbearing symbolism, the cryptic language, and the dream-like ambiance are all in the service of motifs that define everyday human struggle, and not just the specific, para-natural circumstances of a tortured author gone missing.

Now, every player will no doubt have their own interpretation of what the story is trying to convey. The very invitation to deliberate is, after all, the hallmark of every great story. But what I personally found compelling is Alan Wake 2’s genuine understanding of mental health issues and how they shape our perception of reality. A lot of stories discuss mental health. A lot of stories dive into what they hope is relatable for mental disorder victims. Only a select few get it right.

So, let’s set up the mise-en-scène again. Go back to the beginning, if you will, as Alan himself is fond of saying. An author and his wife go missing in their holiday destination. A town is haunted by supernatural incidents. There are whispers of dark shadows, monsters that take people away in the cover of night. The biggest monster of them all is the one who controls the narrative. You’ve heard of him. You know his gaze and his name, even “with his face hidden behind a veil of blood.” And so it begins… the nightless night.

Alan Wake 2 begins with a very ominous cutscene, narrated as usual by the titular protagonist. “We all come to a story with hopes and expectations, looking for an answer,” he proclaims. “Sometimes it would be better to live with that hope, without ever knowing the full story.”

Because as a story begins to tread the tenuous line between fiction and reality, we may very well learn that the answers at the bottom of the well were not the ones we were looking for, or ones we were prepared to acknowledge. After all, what is the answer a story can provide? Are stories not ultimately mirrors in whose reflection the audience usually find themselves?

Trying to explain this all-encompassing creative phenomenon, historian Michael Livingston writes, “It is not in the mirror, after all, that we see the truth of ourselves; it is in the eyes of strangers in unfamiliar lands.”

A great story is often defined as having subject matter that deals with the most human issues. Great characters, whether they be swashbuckling heroes of yore with near omnipotence, or rural renditions of the average modern commoner, all struggle with the same things as we do, and it’s through this shared bond that we begin to relate to a character or a story, and read echoes of our own lives into them.

The implication is usually subtle or unrecognizable at first glance. An edgy anti-hero has to fight the monsters within as ferociously as he battles the real monsters that haunt the real world, and he can’t succeed at one without succeeding at the other. A traumatized protagonist comes to terms with their dark past, and in doing so unlocks the strength required to overcome the obstacles along the way.

In Alan Wake 2, there are no such things as heroes and villains, because the monsters we fight are quite literally the chaos within manifest, and the ultimate fight is not for the fate of the world, but for your sanity. The dark place is nothing but a fictitious construct that feeds on your doubts and insecurities. It gorges for more than a decade on the perfectionist author dealing with imposter syndrome. It twists the love of the Lady of the Light until it is a rancid lump of envy and resentment. It takes the holy crusade of good-intentioned townsfolk and turns it into an ideologized murder cult.

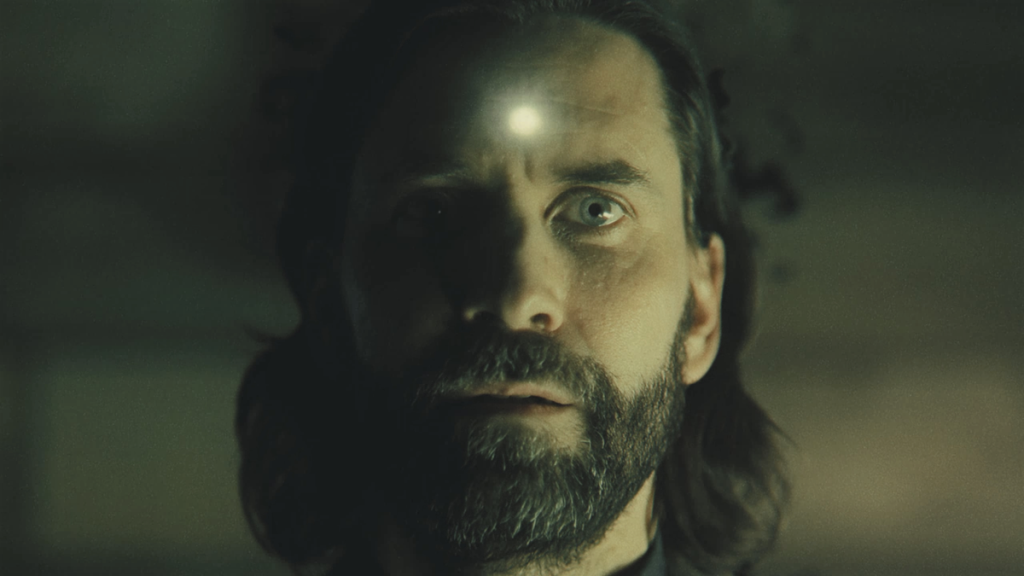

You can certainly read the influence of Jung between the lines. This mental struggle is characteristic of the shadow self, the part of you that you wouldn’t ordinarily acknowledge. Late in Alan Wake 2, it’s revealed that Scratch and Alan are the same person, and it is through Alan’s repressed ego archetype taking over that Scratch is born and let loose in the world.

Another instance that explicitly alludes to this philosophy is Saga getting trapped in the Dark Place. As she tries to reason her way out of this hellscape, her own psyche gives way to another voice, named “Other Saga.” While Saga is trying to solve the riddle and devise a plan to defeat Scratch, Other Saga constantly gets in the way by reminding her of all the things that could go wrong. She speaks aloud her inner anxieties, tries to tarnish the love Saga feels for her daughter Logan, and reinforces the idea that maybe, just maybe, she deserves to be trapped in this place forever.

Alan Wake 2 aptly brings the story to a conclusion by noting that the Dark Place is not a loop, but a spiral. The torturous ordeal you go through as Alan in the Dark Place is not an evil force trying to entrap you. It’s implied time and again that Alan is in control of this narrative, and can rewrite it as he sees fit. He might even have been able to write himself out of the Dark Place if it weren’t for Scratch constantly getting in the way. Mr. Door’s ultimate revelations near the end of the story are a chilling reminder of that. “I don’t even think you know who’s under your masks,” he tells Alan. “But you know how to make things difficult for yourself. All these rules… endless, convoluted loops you insist on going through.”

Alan Wake can’t and won’t write himself out of the Dark Place, because every iteration of the story has to play out perfectly. Because the self-doubting author, now clothed in the power to turn his prose to reality, can’t find a way to write a version of the story where he and his wife Alice come out of the woods untouched. And so, he tortures himself, feeding his doubts and insecurities and getting locked into a seemingly eternal struggle with his shadow archetype. The story soon turns a darker turn, becoming a gritty horror show that highlights Alan’s spiral madness.

The idea that all of this plays out seamlessly in the context of a video game and its supernatural undercurrents is an achievement I’d yet to see in any story, in any shape or form. As someone who’s had to deal with these issues extensively in his life, having been clinically diagnosed with both OCD and anxiety disorder, I can say that the spiral nature of the dark place is a perfect analogy for mental health diseases like depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Some expect you to snap out of it. Some realize it’s a difficult battle. But rarely do we see it depicted with such nuance and accuracy. That the mental rituals you go through, whether they be catechism you repeat without end or dark thoughts that lead you to isolation, are not a loop but a spiral seems to be the perfect analogy for our own inner monster of chaos, fed or hungered in an unending spiral. Yes, Alan could’ve written himself out of the Dark Place any time he wished, but he didn’t. And in ways that may elude understanding or seem counter-intuitive, we understand why.

You can try to depict mental health problems in art, but you will never come close to the experience of actually living it.

Alan Wake 2 is a game that came pretty close… unnervingly so. And for that achievement alone, Sam Lake and the team at Remedy should be proud.