Image: “The School of Athens” (1511) by High Renaissance painter Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino

The divine is dead; men saw to its execution. They replaced the moral teachings of Christianity with a void of potential, and in doing so precipitated the most disastrous display of human savagery the world had ever seen.

If these words are familiar to you — and the point of this new musing is to prove that they’re not, at least to most people — it is because you’ve heard them being interpreted in one form or another as the teachings of the 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. The absurdist moralizer. The paradoxical nihilist. The man you’re taught to fear as a specimen who proves, rather unironically, that nothing besides calamity could come of this uniquely human faculty, what we the less astute would call thinking.

Calamitous seems to be the right word, not only because of the great thinker’s own fate but what he ended up inspiring. This is a man who looked into the abyss long enough to have it stare back at him, and lived to tell the tale of this encounter despite discouraging others to do the same. And this is also the man who, heedless of his own unfathomable resilience, lost that fragile hold on sanity over scenery that wouldn’t even give pause to the average person. (Look up The Turin Horse and Walter Kaufmann’s Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist)

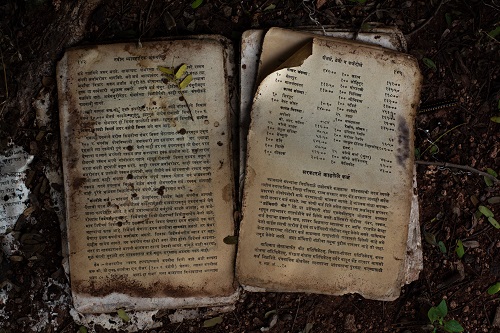

And so, Nietzsche says, history’s natural inclination is to turn the divine into an archaic tapestry, hung as an ornamentation of a bygone age, to be cherished alongside other relics of a past that we tentatively revisit in books, monuments, churches, mausoleums, and landmarks to honor what came before, but never quite explore, lest we inadvertently find ourselves facing knowledge that should’ve conveniently been left in the history’s dustbin of old ideas, and the world better for it.

“God is dead,” the German philosopher recurrently insists. “God remains dead, and we have killed him.” That was the first major schism, the first sail untied from the ship’s mast, the severance that turned mankind into a renegade manifestation of chaos, fumbling its way through the dark, hopeful for a dawn that disillusions him of mysticism and relieves him of divination’s curse.

But you see, that’s where it all went wrong. Nietzsche couldn’t have known, for it wasn’t God that mankind was killing. It would not stop there. Oh, it was never fated to stop there. The divine was just the beginning; cognition was the prize.

And to morrow, and to morrow, and to morrow they go, bearing witness to the desolation of a world that has forsaken the wisdom of ages in the hope of deliverance through a tasteless alternative, that of undermining the very intellect divorcing them from a herd of disorderly animals.

It is a strange fate, that we should see the death of the scholar, powerless to stop it. And for no other reason besides people losing interest in the very act of divination. Behold now the army of self-contradicting moralizers, whose only guidance through this treacherous path of faulty reason is the feel of the moment, their sense of right and wrong an innate understanding whose wellspring shall remain an enigma. The most flamboyant display of willful ignorance.

Gaze into their hearts, marred by inner conflict. Peer into their souls, darkened by vice. Contemplate their diversions, a measure against reflection, and their addictions, a measure of fleeting comfort. Watch how wasteful they are in their bearings, and how unwise in their faint reverence for time.

Look further out, beyond the fields, where their cities lie. See their swirling defiance in the face of existential pain. See how they rise every day knowing that regardless of the pain and joy awaiting them, one outcome is almost certainly guaranteed; That faith dwindles as hope drowns, out of what frailty this world is always bound to. And yet these creatures, these creatures don’t fight back against the enveloping shadow. If anything, they cherish it, for what can’t destroy you completely will eventually cease to hurt you altogether. Who wouldn’t embrace the abyss fully but once, and not have to suffer the pain of hope? The inevitability of defeat? The sting of despair, the temptation of triumph?

Who would think and know, fully aware of the pain that succeeds it?

These people think themselves depressed, when they’re merely hopeless. They wail over trivial flukes, when they have no idea what true sorrow is. They decry tyranny, when they unwittingly instigate it. They rail against misfortune, when they deny chance and the twistings of fate. They allude to pain, when they’ve spurned it entirely.

Thus, ever so incrementally, the human turns into a creature of paradox. A creature ruled by whims, defined by his refusal to acknowledge where that briefest hint of sanity comes from, his carefree attitude towards cognition a counterpoint to his muddled desire for significance, his will to power. His only sense of control the chemicals that presently pervade his brain. And the modern human suffers, not in the true sense, not in the noble sense, but he suffers nevertheless.

This embryonic subset of the Neanderthal doesn’t look for answers, as there are no answers to be found. He moves from flower to flower, a dandelion caught in life’s buffeting winds, and hopes that he doesn’t get crushed, violently and suddenly, when this chaotic interlude — supposedly indecipherable in nature — has run its course.

A people who refuse to acknowledge cognition have no use for discernment.

Wonder thou still, dear sage from the ancient world, the philosopher-king atop Parnassus, my Sufi friend from across time, why the world has forsaken thy teachings?